Stall (flight)

- For other uses, see stall.

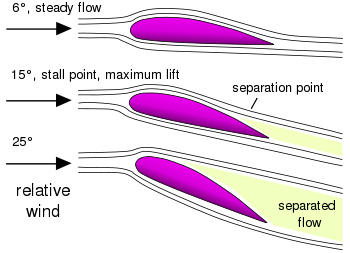

In fluid dynamics, a stall is a reduction in the lift coefficient generated by an airfoil as angle of attack increases. This occurs when the critical angle of attack of the airfoil is exceeded. The critical angle of attack is typically about 15 degrees, but it may vary significantly depending on the airfoil and Reynolds number.

Because stalls are most commonly discussed in connection with aviation, this article discusses stalls mainly as they relate to aircraft, particularly fixed-wing aircraft. Stalls in fixed-wing flight are often experienced as a sudden reduction in lift as the pilot increases angle of attack and exceeds the critical angle of attack (which may be due to slowing down below stall speed in level flight). A stall does not mean that the engine(s) have stopped working, or that the aircraft has stopped moving—the effect is the same even in an unpowered glider aircraft.

Contents |

Formal definition

A stall is a condition in aerodynamics and aviation where the angle of attack increases beyond a certain point such that the lift begins to decrease. The angle at which this occurs is called the critical angle of attack. This critical angle is dependent upon the profile of the wing, its planform, its aspect ratio, and other factors, but is typically in the range of 8 to 20 degrees relative to the incoming wind for most subsonic airfoils. The critical angle of attack is the angle of attack on the lift coefficient versus angle-of-attack curve at which the maximum lift coefficient occurs.

Flow separation begins to occur at small angles of attack while attached flow over the wing is still dominant. As angle of attack increases, the separated regions on the top of the wing increase in size and hinder the wing's ability to create lift. At the critical angle of attack, separated flow is so dominant that further increases in angle of attack produce less lift and vastly more drag.

A fixed-wing aircraft during a stall may experience buffeting or a change in attitude (normally nose down in General aviation aircraft). Most aircraft are designed to have a gradual stall with characteristics that will warn the pilot and give the pilot time to react. For example an aircraft that does not buffet before the stall may have an audible alarm or a stick shaker installed to simulate the feel of a buffet by vibrating the stick fore and aft. The "buffet margin" is, for a given set of conditions, the amount of ‘g’, which can be imposed for a given level of buffet. The critical angle of attack in steady straight and level flight can only be attained at low airspeed. Attempts to increase the angle of attack at higher airspeeds can cause a high speed stall or may merely cause the aircraft to climb.

Any yaw of the aircraft as it enters the stall regime can result in autorotation, which is also sometimes referred to as a 'spin'. Because air no longer flows smoothly over the wings during a stall, aileron control of roll becomes less effective, whilst simultaneously the tendency for the ailerons to generate adverse yaw increases. This increases the lift from the advancing wing and accentuates the probability of the aircraft to enter into a spin.

Depending on the aircraft's design, a stall can expose extremely adverse properties of balance and control; particularly in a prototype.

Graph

The graph shows that the greatest amount of lift is produced as the critical angle of attack is reached (which in early 20th century aviation was called the "burble point"). This angle is 17.5 degrees in this case but changes from airfoil to airfoil. In particular, for aerodynamically thick airfoils (thickness to chord ratios of around 10%) the critical angle is increased compared with a thin airfoil of the same camber. Symmetric airfoils have lower critical angles (but also work efficiently in inverted flight). The graph shows that as the angle of attack exceeds the critical angle, the lift produced by the airfoil decreases.

The information in a graph of this kind is gathered using a model of the airfoil in a wind tunnel. Because aircraft models are normally used, rather than full-size machines, special care is needed to make sure data is taken in the same Reynolds number regime (or scale speed) as in free flight. The separation of flow from the upper wing surface at high angles of attack is quite different at low Reynolds number from that at the high Reynolds numbers of real aircraft. High pressure wind tunnels are one solution to this problem. Steady operation of an aircraft at an angle of attack above the critical angle is not generally possible because, after exceeding the critical angle, the loss of lift from the wing causes the nose of the aircraft to fall, reducing the angle of attack again. This nose drop, independent of control inputs, indicates the pilot has actually stalled the aircraft.[1][2]

This graph shows the stall angle, yet in practice most pilot operating handbooks (POH) or generic flight manuals describe stalling in terms of airspeed. This is because all aircraft are equipped with an airspeed indicator, but fewer aircraft have an angle of attack indicator. An aircraft's stalling speeds is published by the manufacturer (and is required for certification by flight testing) for a range of weights and flap positions, but the stalling angle of attack is not published.

As speed reduces, angle of attack has to increase to keep lift constant until the critical angle is reached. The airspeed at which this angle is reached is the (1g, unaccelerated) stalling speed of the aircraft in that particular configuration. Deploying flaps/slats decreases the stall speed to allow the aircraft to take off and land at a lower speed.

Aerodynamic description of a stall

Stalling an airplane

An airplane can be made to stall in any pitch attitude or bank angle or at any airspeed but is commonly practiced by reducing the speed to the unaccelerated stall speed, at a safe altitude. Unaccelerated (1g) stall speed varies on different aeroplanes and is represented by colour codes on the air speed indicator. As the plane flies at this speed the angle of attack must be increased to prevent any loss of altitude or gain in airspeed (which corresponds to the stall angle described above). The pilot will notice the flight controls have become less responsive and may also notice some buffeting, a result of the turbulent air separated from the wing hitting the tail of the airplane.

In most light aircraft, as the stall is reached the aircraft will start to descend (because the wing is no longer producing enough lift to support the aeroplane's weight) and the nose will pitch down. Recovery from this stalled state usually involves the pilot decreasing the angle of attack and increasing the air speed, until smooth air flow over the wing is resumed. Normal flight can be resumed once recovery from the stall is complete.[3] The manoeuvre is normally quite safe and if correctly handled leads to only a small loss in altitude (50'-100'). It is taught and practised in order for pilots to recognize, avoid, and recover from stalling the airplane.[4] A pilot is required to demonstrate competency in controlling an aircraft during and after a stall for certification,[5] and it is a routine manoeuvre for pilots when getting to know the handling of a new aircraft type. The only dangerous aspect of a stall is a lack of altitude for recovery.

A special form of asymmetric stall in which the aircraft also rotates about its yaw axis is called a spin. A spin can occur if an aircraft is stalled and there is an asymmetric yawing moment applied to it.[6] This yawing moment can be aerodynamic (sideslip angle, rudder, adverse yaw from the ailerons), thrust related (p-factor, one engine inoperative on a multi-engine non-centreline thrust aircraft), or from less likely sources such as severe turbulence. The net effect is that one wing is more deeply stalled than the other and the aircraft descends rapidly while rotating and some aircraft cannot recover from this condition without correct pilot control inputs (which must stop yaw) and loading.[7] A new solution to the problem of difficult (or impossible) stall-spin recovery is provided by the ballistic parachute recovery system.

The most common stall-spin scenarios occur on takeoff (departure stall) and during landing (base to final turn) because of insufficient airspeed during these manoeuvres. Stalls also occur during a go-around manoeuvre if the pilot does not properly respond to the out-of-trim situation resulting from the transition from low power setting to high power setting at low speed.[8] Stall speed is increased when the upper wing surfaces are contaminated with ice or frost creating a rougher surface.

Stalls do not derive from airspeed and can occur at any speed -but only if the wings have too high an angle of attack. Attempting to increase the angle of attack at 1g by moving the control column back normally causes the aircraft to rise. However aircraft often experience higher g, for example when turning steeply or pulling out of a dive. In these cases, the wings are already operating at a higher angle of attack to create the necessary force (derived from lift) to accelerate in the desired direction. Increasing the g loading still further, by pulling back on the controls, can cause the stalling angle to be exceeded -even though the aircraft is flying at a high speed.[9] These "high speed stalls" produce the same buffeting characteristics as 1g stalls and can also initiate a spin if there is also any yawing.

Symptoms of an approaching stall

One symptom of an approaching stall is slow and sloppy controls. As the speed of the aeroplane decreases approaching the stall, there is less air moving over the wing and therefore less air will be deflected by the control surfaces (ailerons, elevator and rudder) at this slower speed. Some buffeting may also be felt from the turbulent flow above the wings as the stall is reached. The stall warning will sound, if fitted, in most aircraft 5 to 10 knots above the stall speed.[10]

Stalling characteristics

Different aircraft types have different stalling characteristics. A benign stall is one where the nose drops gently and the wings remain level throughout. Slightly more demanding is a stall where one wing stalls slightly before the other, causing that wing to drop sharply, with the possibility of entering a spin. A dangerous stall is one where the nose rises, pushing the wing deeper into the stalled state and potentially leading to an unrecoverable deep stall. This can occur in some T-tailed aircraft where the turbulent airflow from the stalled wing can blanket the control surfaces at the tail.

“Stall speed”

Stalls depend only on angle of attack, not airspeed. Because a correlation with airspeed exists, however, a "stall speed" is usually used in practice. It is the speed below which the airplane cannot create enough lift to sustain its weight in 1g flight. In steady, level flight (1g), the faster an airplane goes, the less angle of attack it needs to hold the airplane up (i.e., to produce lift equal to weight). As the airplane slows down, it needs to increase angle of attack to create the same lift (equal to weight). As the speed slows further, at some point the angle of attack will be equal to the critical (stall) angle of attack. This speed is called the "stall speed". The angle of attack cannot be increased to get more lift at this point and so slowing below the stall speed will result in a descent. And so, airspeed is often used as an indirect indicator of approaching stall conditions. The stall speed will vary depending on the airplane's weight and configuration (flap setting, etc.).

There are multiple V speeds which are used to indicate when a stall will occur:

- VS: the computed stalling speed with flaps retracted at design speed. Often has the same value as VS1.

- VS0: the stalling speed or the minimum steady flight speed in landing configuration (full flaps, landing gear down, spoiler retracted).

- VS1: the stalling speed or the minimum steady flight speed in a specific configuration (usually a "clean" configuration with flaps, landing gear and spoilers all retracted).

- VSR: reference stall speed.

- VSR0: reference stall speed in the landing configuration.

- VSR1: reference stall speed in a specific configuration.

- VSW: speed at which onset of natural or artificial stall warning occurs.

On an airspeed indicator, the bottom of the white arc indicates VS0 at maximum weight, while the bottom of the green arc indicates VS1 at maximum weight. While an aircraft's VS speed is computed by design, its VS0 and VS1 speeds must be demonstrated empirically by flight testing.[11]

Accelerated and turning flight stall

An accelerated stall is a stall that occurs while the aircraft is experiencing a load factor higher than 1 (1g), for example while turning or pulling up from a dive. In these conditions, the aircraft stalls at higher speeds than the normal stall speed (which always refers to straight and level flight).[12]

Considering for example a banked turn, the lift required is equal to the weight of the aircraft plus extra lift to provide the centripetal force necessary to perform the turn, that is:[13][14]

where:

= lift

= lift = load factor (greater than 1 in a turn)

= load factor (greater than 1 in a turn) = weight of the aircraft

= weight of the aircraft

In order to achieve the extra lift, the lift coefficient, and so the angle of attack, will have to be higher than it would be in straight and level flight at the same speed. Therefore, given that the stall always occurs at the same critical angle of attack,[15] by increasing the load factor (e.g. by tightening the turn) such critical angle - and the stall - will be reached with the airspeed remaining well above the normal stall speed[13] , that is:[16][17]

where:

= stall speed

= stall speed = stall speed of the aircraft in straight, level flight

= stall speed of the aircraft in straight, level flight = load factor

= load factor

It should be noted that, according to FAA's terminology, the above example illustrates a so-called turning flight stall, while the term accelerated is used to indicate an accelerated turning stall only, that is a turning flight stall where the airspeed decreases at a given rate.[18]

A notable example of air accident involving a low-altitude turning flight stall is the 1994 Fairchild Air Force Base B-52 crash.

Deep stall

A deep stall (or super-stall) is a dangerous type of stall that affects certain aircraft designs,[19] notably those with a T-tail configuration. In these designs, the turbulent wake of a stalled main wing "blankets" the horizontal stabilizer, rendering the elevators ineffective and preventing the aircraft from recovering from the stall.

Although effects similar to deep stall had long been known to occur on many aircraft designs, the name first came into widespread use after a deep stall led to the crash of the prototype BAC 1-11 G-ASHG on October 22nd, 1963, killing its crew. This led to changes to the aircraft, including the installation of a stick shaker (see below) in order to clearly warn the pilot of the problem before it occurred. Stick shakers are now a part of all commercial airliners. By sheer coincidence, also on October 22nd, 1963, a Tu-134 was lost in a flight test due to the same cause. Nevertheless, the problem continues to cause accidents; on June 3rd 1966 a Hawker Siddeley Trident (G-ARPY)[1] was lost to deep stall; deep stall is suspected to be cause of another Trident (G-ARPI) crash on June 18th 1972; on April 3rd 1980 a prototype of the Canadair Challenger business jet entered deep stall during testing, killing one of the test pilots who was unable to leave the plane in time[20] and on July 26th 1993 a Canadair CRJ-100 was lost in flight test due to a deep stall.[21]

Deep stall is possible with some sailplanes, as their most common designs are T-tail configurations. The IS-29 glider is one of the gliders that are vulnerable to deep stalls when the CG and the overall weight are between certain limits.

In the early 1980s, a Schweizer SGS 1-36 sailplane was modified for NASA's controlled deep-stall flight program.[22]

A different type of stall affecting the F-16 fighter is also known as a deep stall because of its similar difficulty in recovery, but for a different reason. The aircraft is designed to be inherently unstable, which when kept under control by its "fly-by-wire" system allows for higher maneuverability. However, this design, coupled with the intent of the control computer to keep the fighter level, prevents the aircraft from pitching nose-down in a stall, which would allow the pilot to recover given sufficient altitude. This is known as a deep stall because the elevators are rendered useless by the flight computer even though, unlike a T-tail, air does contact the elevators, and even with the computer disabled it is difficult to recover from (the pilot must "rock" the aircraft with elevator input until it pitches nose-down, which can take several seconds).

Stall warning and safety devices

Aeroplanes can be equipped with devices to prevent or postpone a stall or to make it less (or in some cases more) severe, or to make recovery easier.

- An aerodynamic twist can be introduced to the wing with the leading edge near the wing tip twisted downward. This is called washout and causes the wing root to stall before the wing tip. This makes the stall gentle and progressive. Since the stall is delayed at the wing tips, where the ailerons are, roll control is maintained when the stall begins.

- A stall strip is a small sharp-edged device which, when attached to the leading edge of a wing, encourages the stall to start there in preference to any other location on the wing. If attached close to the wing root it makes the stall gentle and progressive; if attached near the wing tip it encourages the aircraft to drop a wing when stalling.

- A stall fence is a flat plate in the direction of the chord to stop separated flow progressing out along the wing[23]

- Vortex generators, tiny strips of metal or plastic placed on top of the wing near the leading edge that protrude past the boundary layer into the free stream. As the name implies they energize the boundary layer by mixing free stream airflow with boundary layer flow thereby creating vortices, this increases the inertia of the boundary layer. By increasing the inertia of the boundary layer airflow separation and the resulting stall may be delayed.

- An anti-stall strake is a leading edge extension which generates a vortex on the wing upper surface to postpone the stall.

- A stick pusher is a mechanical device which prevents the pilot from stalling an aeroplane. It pushes the elevator control forwards as the stall is approached, causing a reduction in the angle of attack. Generically, a stick pusher is known as a stall identification device or stall identification system.[24]

- A stick shaker is a mechanical device which shakes the pilot's controls to warn of the onset of stall.

- A stall warning is an electronic or mechanical device which sounds an audible warning as the stall speed is approached. The majority of aircraft contain some form of this device that warns the pilot of an impending stall. The simplest such device is a stall warning horn, which consists of either a pressure sensor or a movable metal tab that actuates a switch, and produces an audible warning in response.

- An Angle-Of-Attack (AOA) Indicator or A.K.A Lift Reserve Indicator is a pressure differential instrument that integrates airspeed and angle of attack into one instantaneous, continuous readout. An AOA indicator provides a visual display of the amount of available lift throughout its slow speed envelope regardless of the many variables which act upon an aircraft. This indicator is immediately responsive to changes in speed, angle of attack and wind conditions and automatically compensates for aircraft weight, altitude, and temperature.

- An angle of attack limiter or an "alpha" limiter is a flight computer that automatically prevents pilot input from causing the plane to rise over the stall angle. Some alpha limiters can be disabled by the pilot.

Stall warning systems often involve inputs from a broad range of sensors and systems to include a dedicated angle of attack sensor.

Blockage, damage, or inoperation of stall and angle of attack (AOA) probes can lead to the stall warning becoming unreliable and cause the stick pusher, overspeed warning, autopilot and yaw damper to malfunction.[25]

If a forward canard is used for pitch control, rather than an aft tail, the canard is designed to meet the airflow at a slightly greater angle of attack than the wing. Therefore, when the aircraft pitch increases abnormally, the canard will usually stall first, causing the nose to drop and so preventing the wing from reaching its critical AOA. Thus the risk of main wing stalling is greatly reduced. Unfortunately if the main wing stalls, recovery becomes difficult as the canard is more deeply stalled and angle of attack increases rapidly.[26]

If an aft tail is used, the wing is designed to stall before the tail. In this case, the wing can be flown at higher lift coefficient (closer to stall) to produce more overall lift.

Most military combat aircraft have an angle of attack indicator among the pilot's instruments which lets the pilot know precisely how close to the stall point the aircraft is. Modern airliner instrumentation may also measure angle of attack although this information may not be directly displayed on the pilot's display, instead driving a stall warning indicator or giving performance information to the flight computer (for fly by wire systems).

Flight beyond the stall

As the wing stalls aileron effectiveness is reduced making the plane hard to control and increasing the risk of a spin starting. Steady flight beyond the stalling angle (where the coefficient of lift is largest) requires engine thrust to replace lift as well as alternate controls to replace the loss of effectiveness of the ailerons. For high powered aircraft, the loss of lift (and increase in drag) beyond the stall angle is less of a problem than maintaining control. Control can be provided by vectored thrust as well as a rolling stabilator (or "taileron") and the enhanced manoeuvering capability by flights at very high angles of attack can provide a tactical advantage for military fighters such as the F-22 Raptor. The highest angle of attack in sustained flight so far demonstrated was 70 degrees in the X-31 at the Dryden Flight Research Center.[27]

Spoilers

Except for flight training, airplane testing and aerobatics, a stall is usually an undesirable event. Spoilers (sometimes called lift dumpers), however, are devices that are intentionally deployed to create a carefully controlled flow separation over part of an aircraft's wing in order to reduce the lift it generates, increase the drag, and allow the aircraft to descend more rapidly without gaining speed.[28] Spoilers are also deployed asymmetrically (one wing only) to enhance roll control. Spoilers can also be used on aborted take-offs and after main wheel contact on landing to increase the aircraft's weight on its wheels for better braking action.

Unlike powered airplanes, which can control descent by increasing or decreasing thrust, gliders have to increase drag to increase the rate of descent. In high performance gliders spoiler deployment is extensively used to control the approach to landing.

Spoilers can also be thought of as "lift reducers" because they reduce the lift of the wing in which the spoiler resides. For example, an uncommanded roll to the left could be reversed by raising the right wing spoiler (or only a few of the spoilers present in large airliner wings). This has the advantage of avoiding the need to increase lift in the wing that is dropping (which may bring that wing closer to stalling).

See also

- Wing twist

- Air safety

- Coefficient of lift

- Compressor stall

- Spin (flight)

- Spoiler (aeronautics)

- Dynamic stall

- Coffin corner (aviation)

Notes

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Sections 5.28 and 16.48

- ↑ Anderson, J.D., A History of Aerodynamics, p 296-311

- ↑ FAA Airplane flying handbook ISBN 978-1-60239-003-4 Chapter4 Page 7

- ↑ 14 CFR part 61

- ↑ Federal Aviation Regulations Part25 section 201

- ↑ FAA Airplane flying handbook ISBN 978-1-60239-003-4 Chapter4 pages 12-16

- ↑ 14 CFR part 23

- ↑ FAA Airplane flying handbook ISBN 978-1-60239-003-4 Chapter4 page 11-12

- ↑ FAA Airplane flying handbook ISBN 978-1-60239-003-4 Chapter4 Page 9

- ↑ Federal Aviation Regulations part 25 section 207

- ↑ Flight testing of fixed wing aircraft. Ralph D. Kimberlin ISBN 978-1-56347-564-1

- ↑ Brandon, John. "Airspeed and the properties of air". Recreational Aviation Australia Inc. http://www.auf.asn.au/groundschool/umodule2.html#accel_stall. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Section 5.22

- ↑ McCormick, Barnes W. (1979), Aerodynamics, Aeronautics and Flight Mechanics, p.464, John Wiley & Sons, New York ISBN 0-471-03032-5

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Sections 5.8 and 5.22

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, Equation 14.11

- ↑ McCormick, Barnes W. (1979), Aerodynamics, Aeronautics and Flight Mechanics, Equation 7.57

- ↑ "Part 23 - Airworthiness Standards: §23.203 Turning flight and accelerated turning stalls". Federal Aviation Administration. February 1996. http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=3a0a07257d2f5a7f42a2c1920e63f263&rgn=div8&view=text&node=14:1.0.1.3.10.2.65.40&idno=14. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ↑ "What is the super-stall?". Aviationshop. http://www.aviationshop.com.au/avfacts/editorial/tipstall/. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19800403-1

- ↑ http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19930726-2

- ↑ Schweizer-1-36 index: Schweizer SGS 1-36 Photo Gallery Contact Sheet

- ↑ http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Theories_of_Flight/Transonic_Wings/TH20G6.htm

- ↑ US Federal Aviation Administration, Advisory Circular 25-7A Flight Test Guide for Certification of Transport Category Airplanes, paragraph 228

- ↑ Harco Probes Still Causing Eclipse Airspeed Problems

- ↑ Airplane stability and control By Malcolm J. Abzug, E. Eugene Larrabee Chapter 17 ISBN 0-521-80992-4

- ↑ http://www.dfrc.nasa.gov/gallery/Photo/X-31/HTML/EC94-42478-3.html

- ↑ http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/K-12/airplane/spoil.html

References

- Anderson, J.D., A History of Aerodynamics (1997). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 66955 3

- Chapter 4, "Slow Flight, Stalls, and Spins," in the Airplane Flying Handbook. (FAA H-8083-3A)

- Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0 273 01120 0

- Stengel, R. (2004), Flight Dynamics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-114-7-2

- Alpha Systems AOA Website for information on AOA and Lift Reserve Indicators [2]

- How Does a Stick Shaker Sensor Work? [3]

- 4239-01 Angle of Attack (AoA) Sensor Specifications [4]

- Airplane flying Handbook. Federal Aviation Administration ISBN 1-60239-003-7 Pub. Skyhorse Publishing Inc.

- http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgAdvisoryCircular.nsf/0/a2fdf912342e575786256ca20061e343/$FILE/AC61-67C.pdf

- Prof. Dr Mustafa Cavcar, "Stall Speed" [5]